(Author’s Note: This is an excerpt from my upcoming book, Trailblazers: How Ordinary People Protect Extraordinary Places. While the conservation world often highlights scientists and activists (and rightfully so), this chapter makes a case for the creatives, the artists, photographers, and storytellers, who shape how we feel about nature. Thanks for reading, and if you want to follow my journey to publication, please consider subscribing!).

***

When we picture conservation, we often picture people in boots: scientists tracking migration paths, rangers managing fire lines, activists chaining themselves to trees. We picture laws and lawsuits, climate reports and field data. And all of that matters. But it’s not the whole story.

Because long before most people care about a place, they fall in love with it. And falling in love doesn’t usually start with spreadsheets. Our love of a place starts with a photograph, a sentence, a song. A memory passed down, a story well told.

Artists and writers have always played a vital role in conservation. They shape perspective. They make us care about ecosystems so that we can help build the structure needed to preserve them. They capture what science cannot: the feeling of standing beneath an old-growth redwood, the hush of snow falling on a prairie, the grief of watching a species fade, and the joy of seeing one return. Data is valuable, of course, but art reveals to us why it matters on a level that numbers and facts cannot reach.

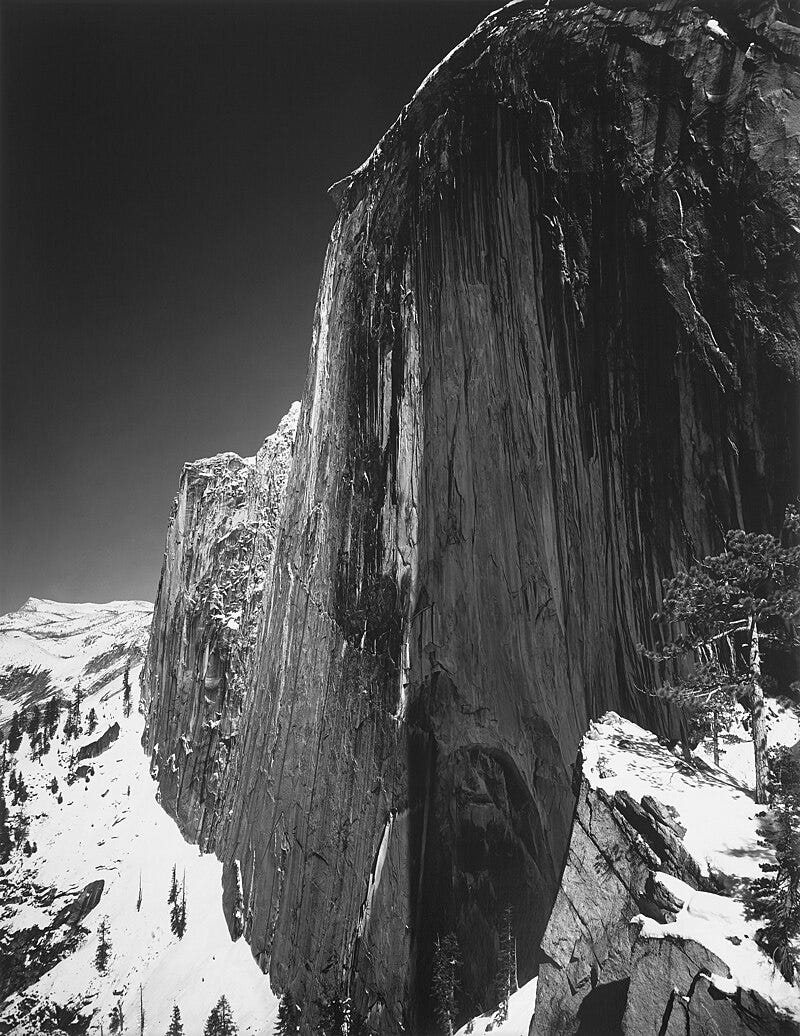

Ansel Adams said "both the grand and intimate aspects of nature can be revealed in the expressive photograph. Both can stir enduring affirmations and discoveries, and can surely help the spectator in his search for identification with the vast world of natural beauty and wonder surrounding him." He understood that his photographs were a bridge, and his images helped inspire a generation to protect wild lands not because of data points, but because of awe.

Image: Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, by Ansel Adams, 1927. Gelatin silver print. Collection: Library of Congress

These aren’t just side effects of environmentalism. They’re the foundation of it. You can’t protect what you don’t feel connected to. The creative act is a form of witness, and sometimes it is a form of resistance.

Terry Tempest Williams once wrote, “Finding beauty in a broken world is creating beauty in the world we find.” Her essays are full of wild grief and wild hope, all acts of witness that refuse to look away from destruction but also refuse to give up on wonder. Her work reminds us that paying attention is not passive: it is both sacred and active.

Even graffiti, protest art, or performance can be a way to say: this place matters.

Artists are the keepers of emotional truth. They give us language when the losses are too big to name. They make the future imaginable when the present feels too heavy. And they remind us, again and again, that conservation is just as much about the survival of meaning as it is about the survival of ecosystems.

Art is also a door. Not everyone feels comfortable reading academic journals or testifying at public hearings, but many people can be moved by a mural, a film, or a short story. Creative work meets people where they are. It brings environmental justice into galleries, into libraries, onto sidewalks, and into classrooms. It belongs not just in the wilderness, but in the heart of every city and suburb, reminding us that nature isn’t something “out there,” but something we are always a part of.

In this way, art democratizes conservation. It opens the conversation to more voices. It allows communities to express their own relationships with place, especially those whose stories have historically been ignored or erased. Through the lens of Indigenous art, diasporic poetry, or grassroots zines, we are reminded that the environment is not a neutral canvas. It is lived, contested, storied ground, and preserving it requires understanding those stories, too.

Creative work also endures. Long after policy documents are outdated and scientific consensus has shifted, the art remains. It anchors a moment in time. It shows future generations what mattered to us, what we cherished, what we feared. It is a way of saying: We were here. We tried to speak for what could not speak for itself.

***

Interested in reading more? Please consider sharing this piece and subscribing - I am working my way towards publication of this entire book. I’d love to share the rest with the world.

Beautiful! 🤍

This reminds me of Jon Muir and other artists who were the ones that actually brought Teddy Roosevelt (and lots of other patrons) to Yellowstone. The creative arts are the front line to the human heart. Thank you for posting such a thoughtful piece